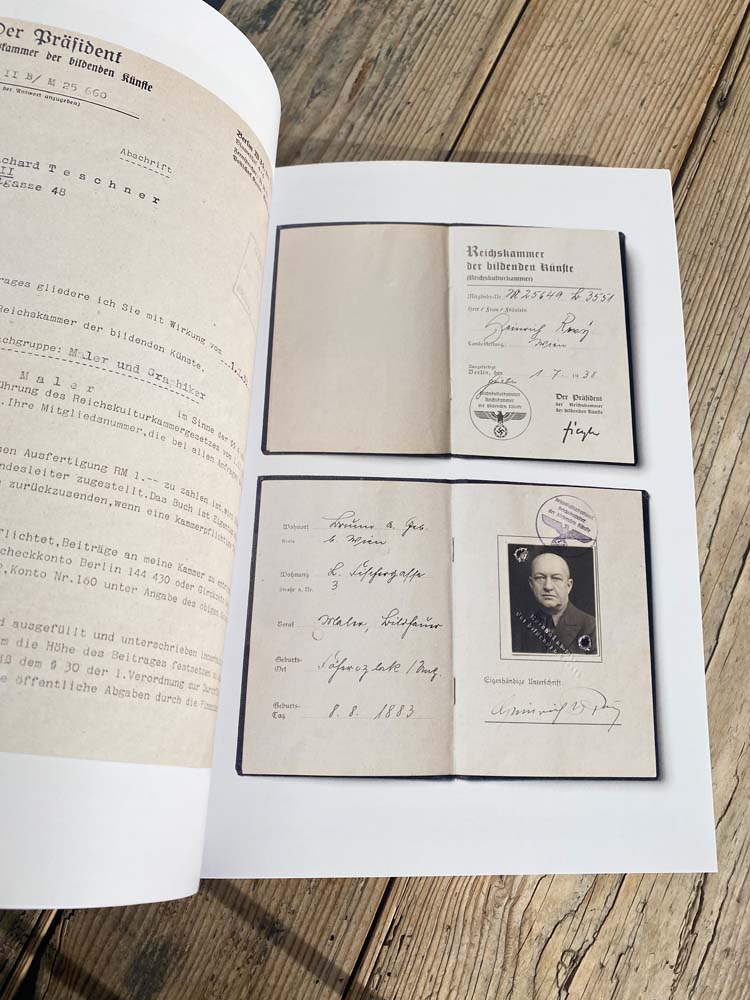

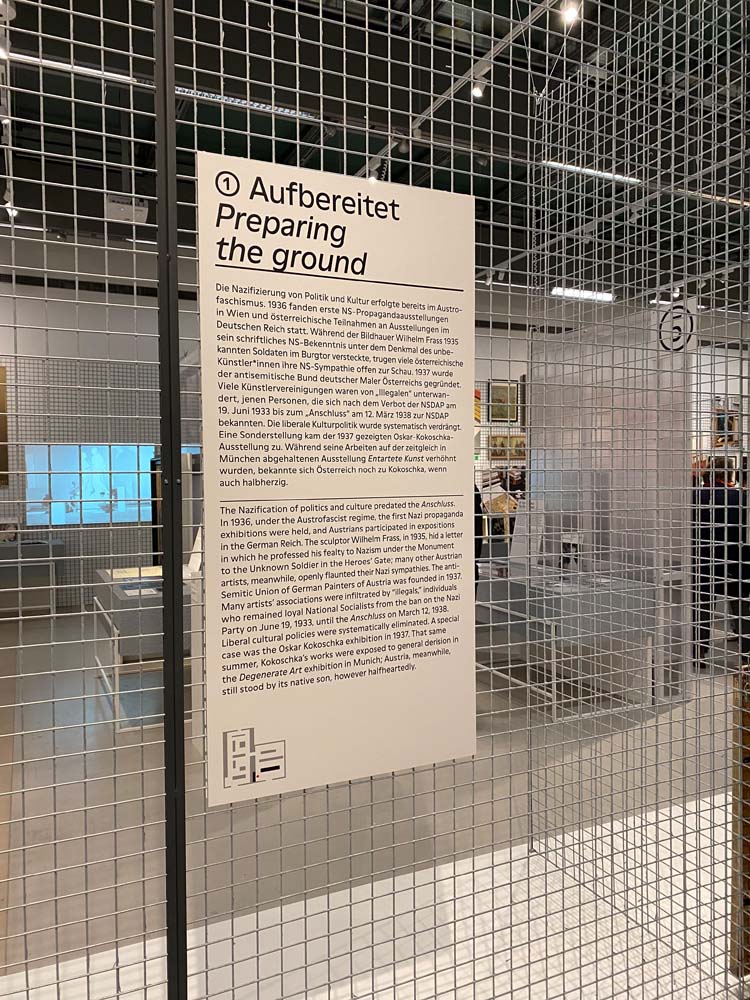

Wien Museum invites us to explore and stimulate a critical discussion about the artistic attitudes of the Nazi regime, the artists working under it, and their artworks. The Reich Chamber of Fine Arts (in DE Reichskammer der bildenden Künste, RdbK) was the most powerful institution for the political control of art under National Socialism, which in those times placed all professional artists under a strict membership rule, after carefully scrutinizing their political affiliations and background. As such, artists with Jewish upbringing or ancestry, political dissidents or anyone considered too avant-garde were rejected and denied membership.

The exhibition “Vienna Falls in Line: The Politics of Art under National Socialism” takes place from October 14th 2021 to April 24th 2022 and is realized in cooperation with the Professional Association of Fine Artists in Austria and the Regional association for Vienna, Lower Austria, Burgenland.

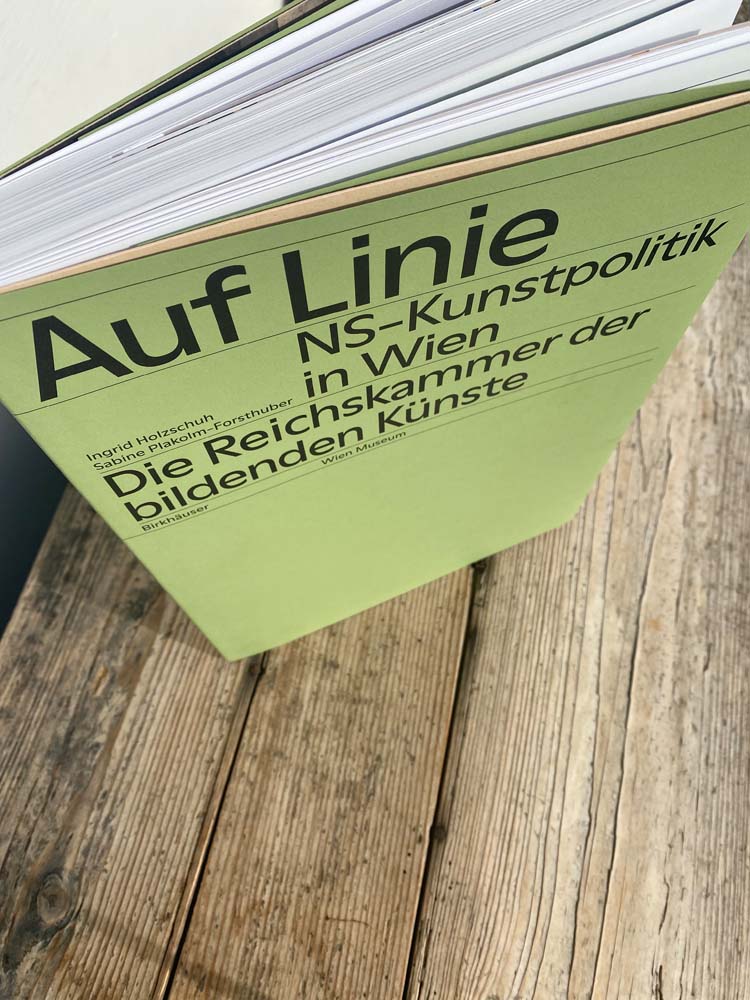

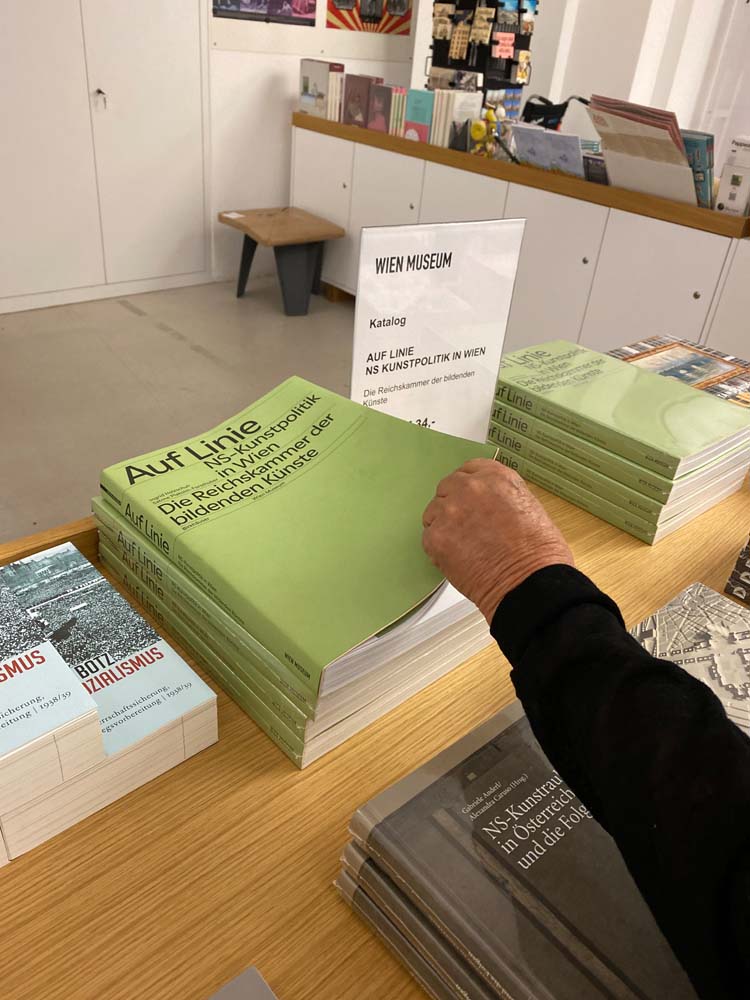

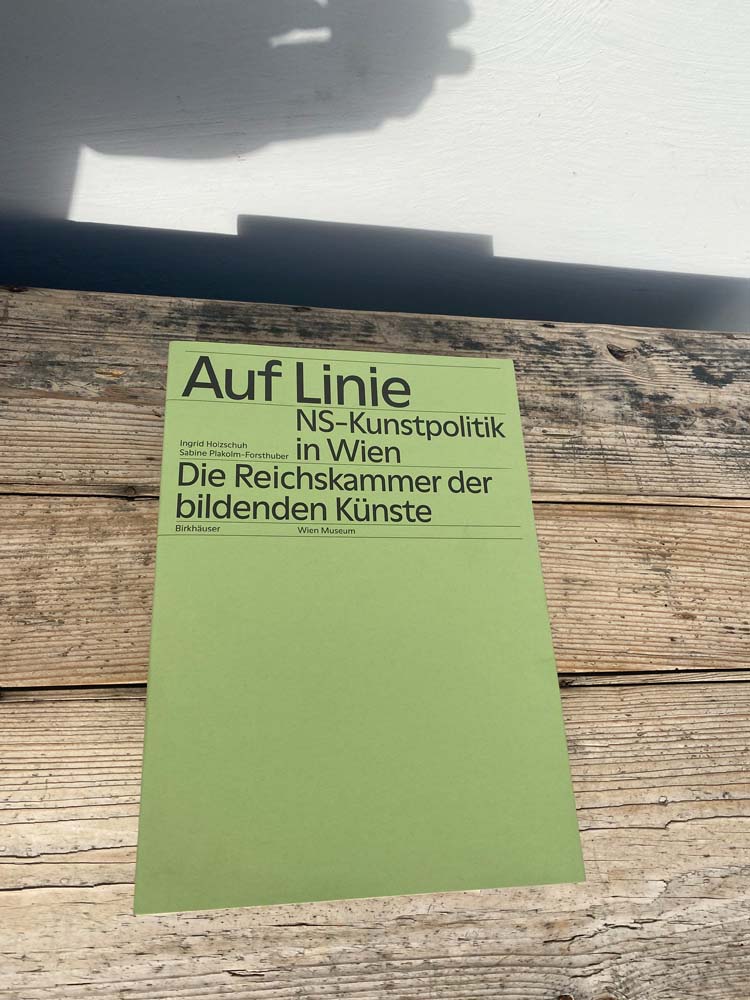

The exhibition’s original objects and documents, categorized into seven sections have also been collected and brought to life in an artbook by the same name “Vienna Falls in Lien: The Politics of Art under National Socialism” (in De: “AUF LINIE. NS KUNSTPOLITIK IN WIEN”) – available to buy here.

Considered in its entirety, the collection offers insight into the rigid 6 system of Nazi art policy, which was characterized by exclusion, oppression, and enforced conformity.”

Christoph Schörkhuber from seite zwei, the agency behind this art book, was kind enough to give us his thoughts on the concept, search for the right materials and design decisions:

“Auf Linie – NS Kunstpolitik in Wien“ (Eng: “Vienna Falls in Line: The Politics of Art under National Socialism”) is a publication on the systemization of art and artists during the NS-Regime. The topics discussed in the publication are still rather sensitive to this day. Finding a factual and objective representation of the content was key in the conceptual process, as well as the design decisions.

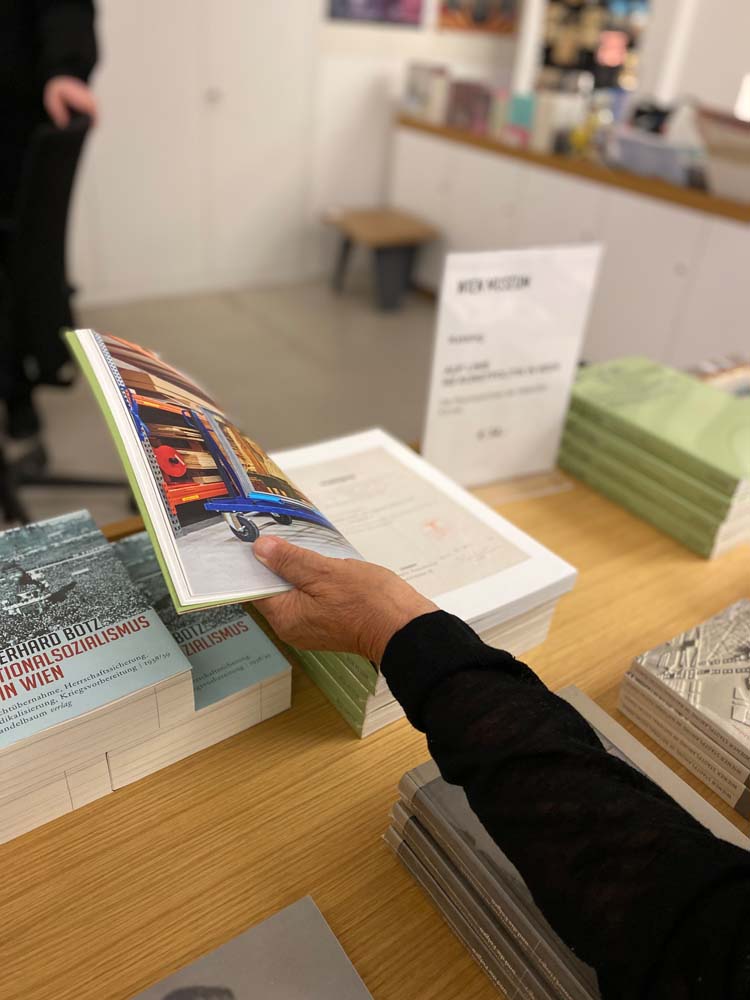

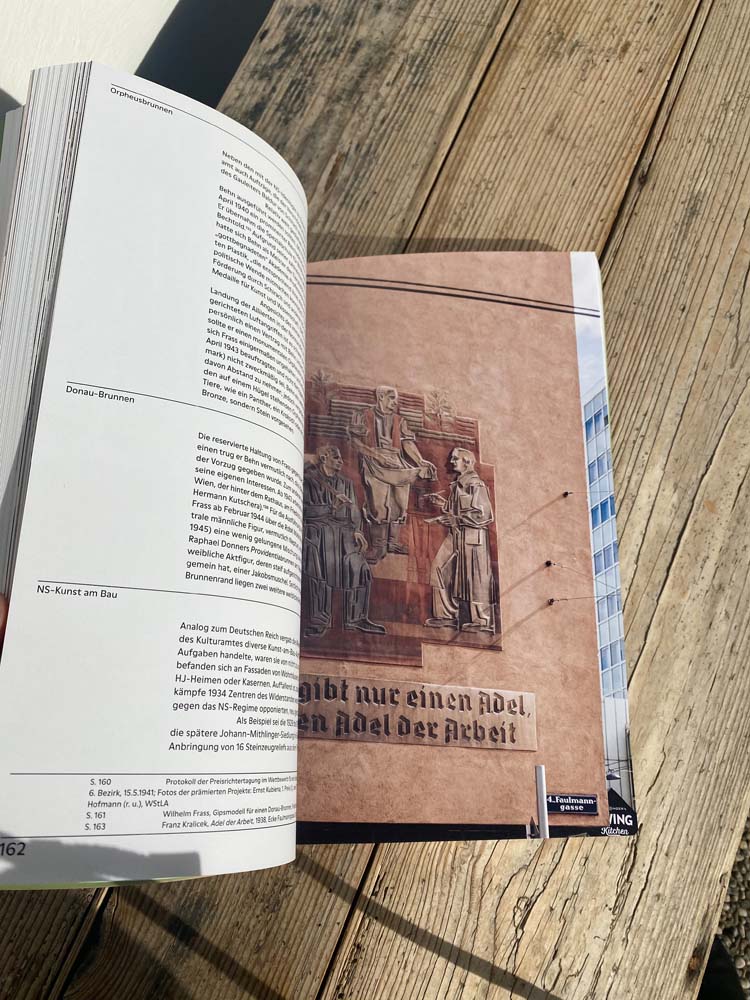

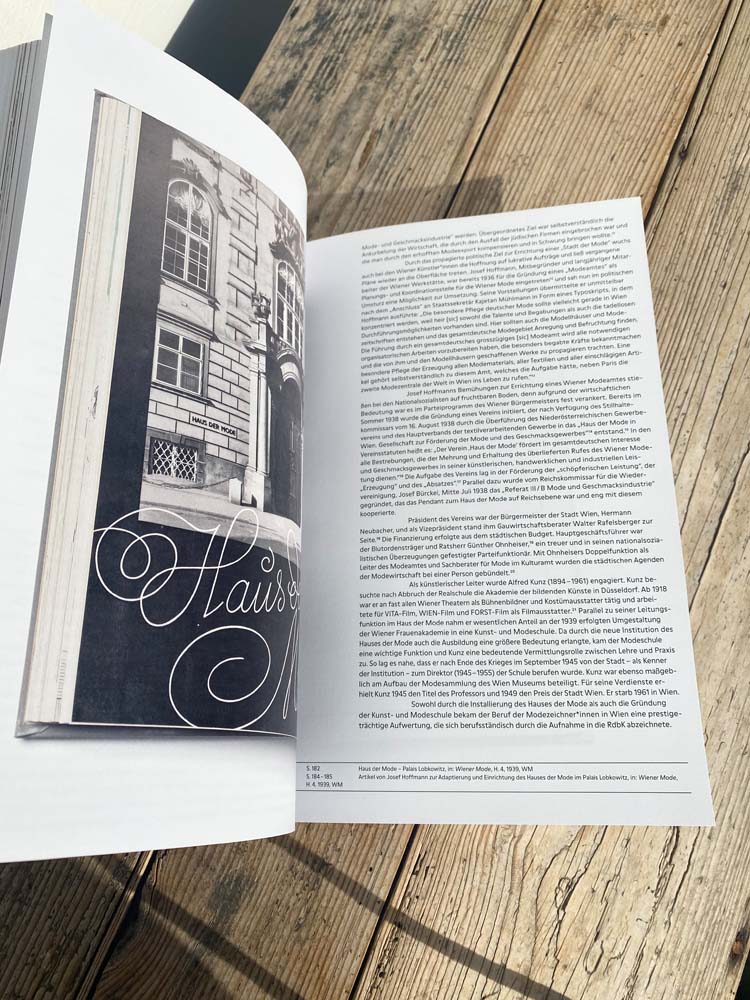

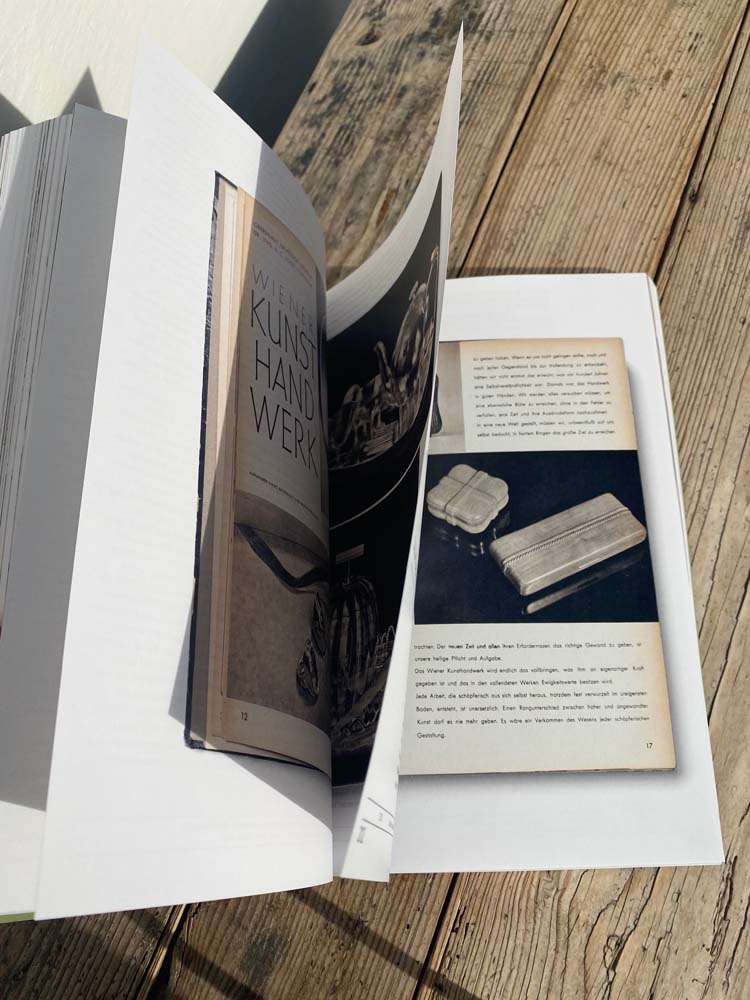

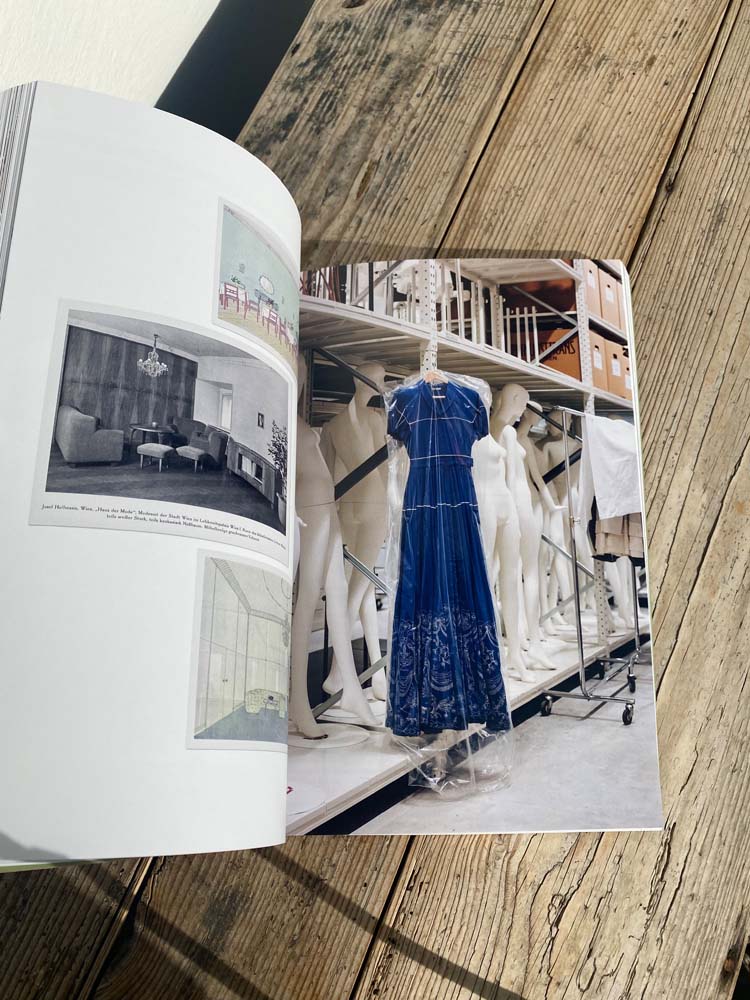

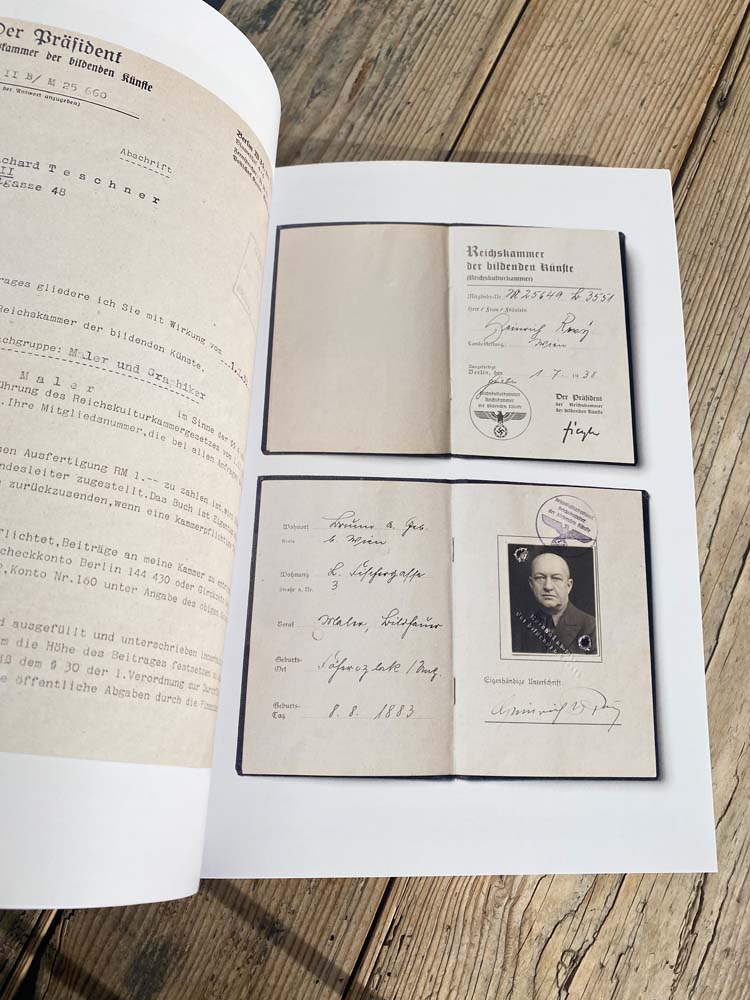

The core structure of the publication creates a strict framework. By using the table of content as a base and sticking to one typeface, a rigid system is being emphasized. Documentary sources are accentuated throughout the publication by giving room to captions, endnotes and indexes. The content is supported by photos of documents and artworks. Documents are shown in the most straightforward way possible by giving no visual context. All artworks are photographed in their respective depot of each museum.

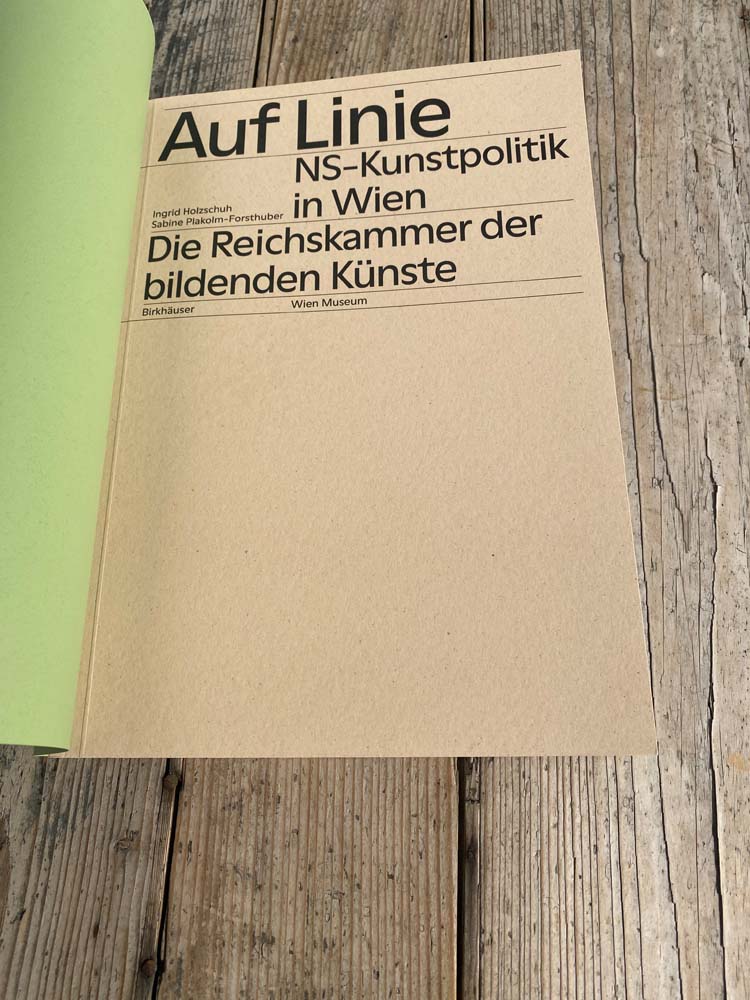

Choosing the right materials was crucial to balance out the objective design approach and support the administrative aspect of the content. Neobond paper is deeply engrained into the Austrian perception of bureaucracy – it had long been in use for various IDs. Choosing it for the dust jacket allows an instant connection to the topic. The material of the cover, Remake Sand paper resembles the texture of folders and complements the other materials with its contrasting rough and detailed texture.

The decision not to show the Nazi works of art in the conventional way emphasizes the difficult handling of collections and museums with works of art from this period on the visual level. At the same time, this layered and accumulated form of presentation – both the objects and the numerous documents – sets the publication apart from common scientific works. It was important to the authors – Ingrid Holzschuh and Sabine Plakolm-Forsthuber – and to the Wien Museum to convey the research results on a strong visual level.”

Sonja Gruber / Wien Museum, publication management

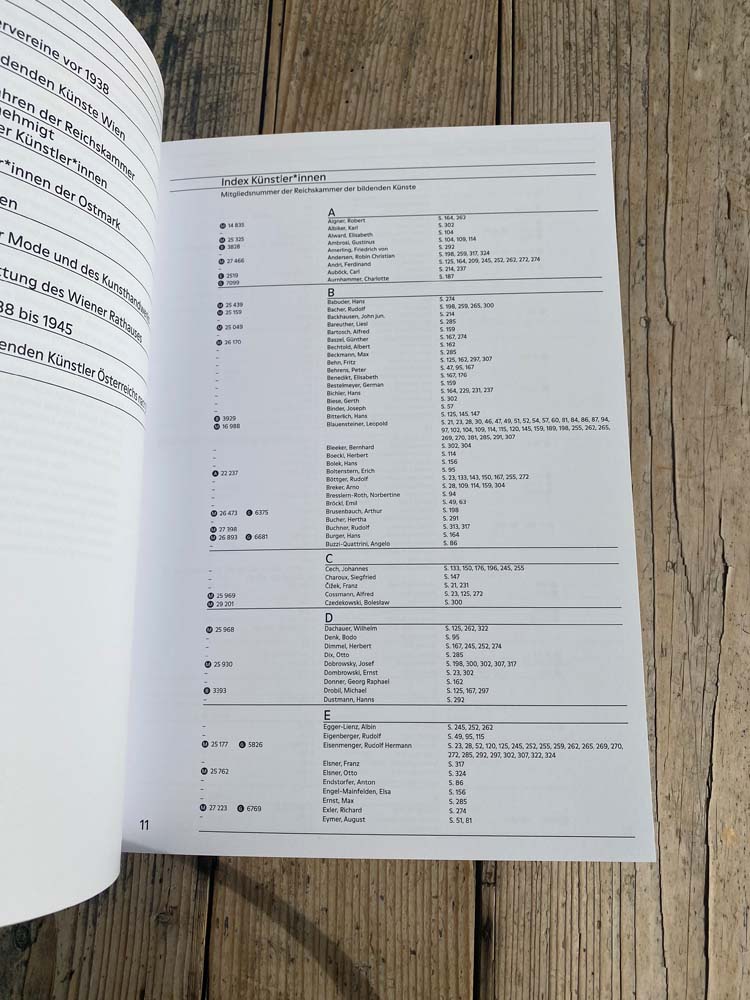

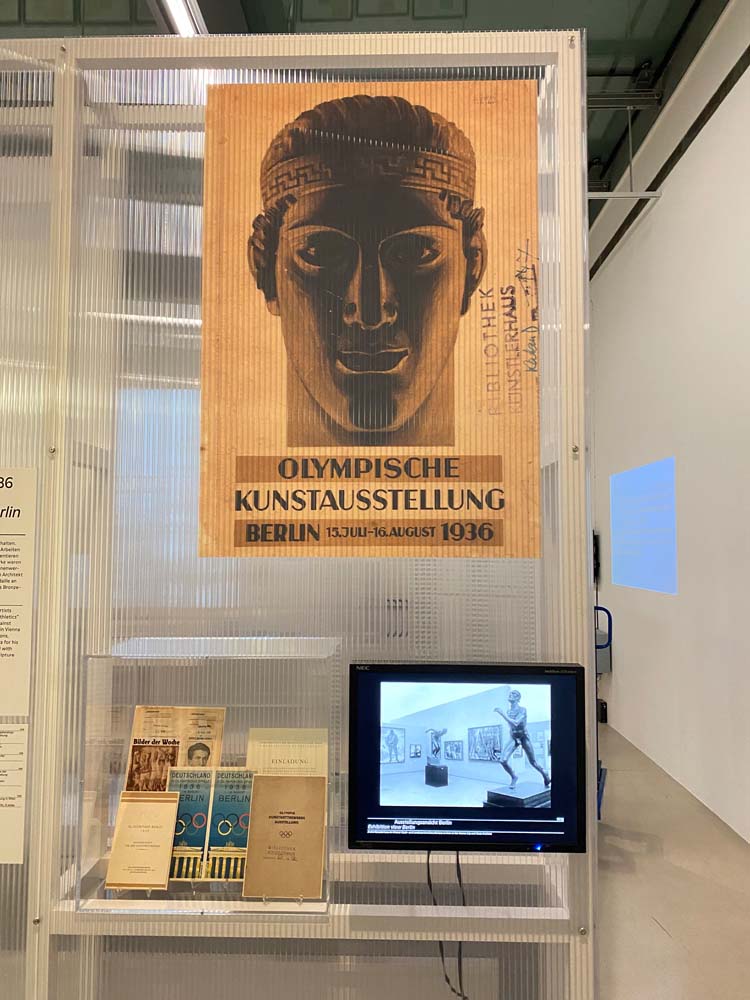

The book and exhibition provide unprecedented access into the files of the Viennese Reichskammer, releaving the names of 3.000 membership files of working artists of Nazi Vienna and their production of political propaganda art. The publication also touches on the “God-Favoured” list (in DE “Gottbegnadeten”) – comprised in 1944 by Hitler and President of the Reich Chamber of Culture and Reich Minister Joseph Goebbles, which included the names of 378 artists regarded indispensable “divinely gifted creators of culture” and as such, except from military service. The artists, coming from all fields of visual art, architecture, literature, music or dramatic arts were held in high esteem and their work regarded an “artistic service to the war”.

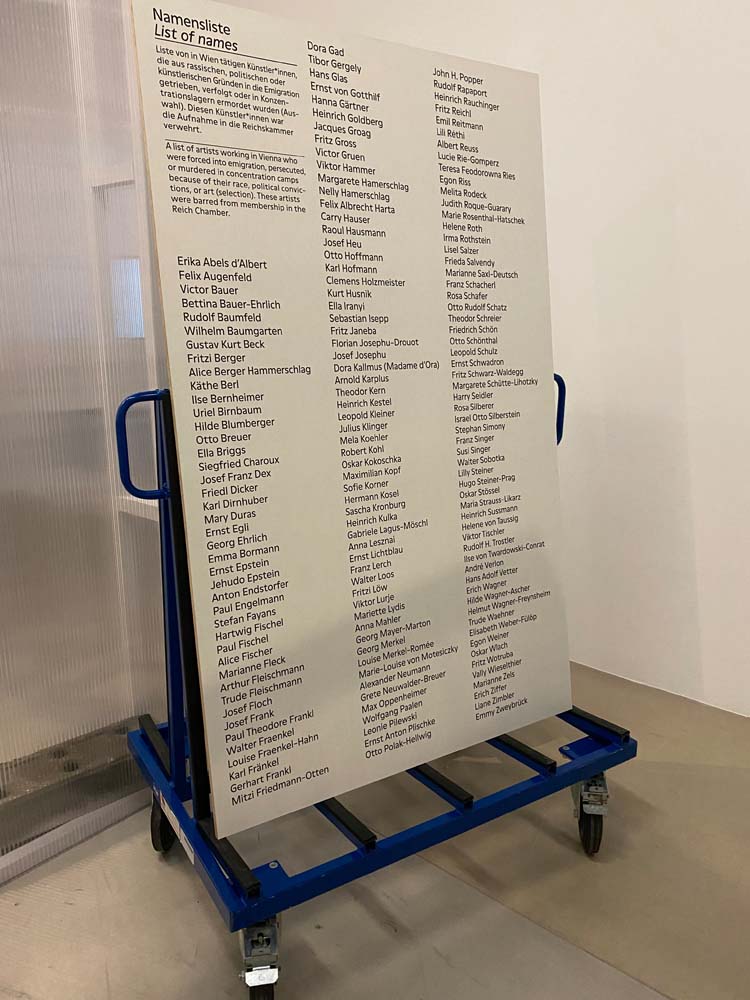

On the other side of the spectrum, the exhibition also commemorates Viennese artists who were forced into emigration, persecuted or executed in concentration camps by the National Socialist regime.

In the preamble of the book, a question is brought up: What to do with all of the Nazi art that takes up space in the depots of museums in Central Europe? As a result from the enforced conformity during the Nazi regime, museums all over Central Europe, whose central tasks are to collect and preserve the past, are flooded with such reminiscences of a hurtful historical chapter. Only in Wien Museum there are around a thousand items – from devoutly crafted kitsch portraits of the “Führer” to pompous sculptures of “Aryan” pseudo-heroes.

And yet, while there are plenty of exhibitions portraying the exile art realized during this time, there are surprisingly few studies on the art officially funded by the National Socialism. Even in artists who have continued their work after the war, these creative pieces are viewed as an embarrassing prelude to the real artistic career, but not as an object of scientific work itself.

As such, the scientific evaluation of the archive of the Chamber of Fine Arts Vienna and exhibition hosted by Wien Museum is a significant contribution in this context. For the first time, the daily reality of the National Socialist art is placed under the scientific microscope and becomes tangible.

The artbook or the exhibition do not claim to have a definite answer to the question of why we should preserve these works of art, but invites to inner reflection, critical discussion and an open dialogue about a reprehensible chapter and a taboo topic in society – precisely the opposite from what art during National Socialism stood for.

Images © Design&Paper